Reading Time – 7 Minutes, Difficulty Level – 1/5

As fond as we are of the British countryside, the open pastures and rolling green hills are not its natural state. Centuries of hunting and clearing of natural landscapes for agriculture has left these islands on the lowest rungs of global biodiversity indices. One of the most pressing issues facing British wildlife is the absence of any apex predator species, which leaves the door open for an over-abundance of both native and invasive herbivore species; predominantly deer. This causes overgrazing and the decline of forests, and the spread of disease among both the deer and hoofed livestock.

Temperate rainforests, such as this one in County Kerry, Ireland, were once widespread across the British Isles, and were home to a great variety of exotic wildlife. Photo by Hauke Musicaloris – CC BY 2.0

Historic ice ages go through cycles of cold and warm periods; glacial and interglacial respectively. During the interglacial periods, higher temperatures caused the great ice sheets to retreat north, exposing the land and releasing moisture. The last interglacial episode (before the one that gave rise to human civilization) was around 120,000 years ago, and the climate in the British isles was very similar to today; temperate and seasonal, with warm summers and chilly winters, plenty of rainfall and prevailing Atlantic winds. However in the absence of intensive grazing, the landscape was a mosaic of dense, temperate rainforests and natural savannahs; habitats which are increasingly difficult to find these days. Living in these wild places was an extraordinary megafaunal assemblage. Elephants and rhinos, moose and bison, hippos and giant elk, horses and antelope. Such an abundance of large prey fed a great many predators, including bears, wolves, hyenas and an astonishing diversity of wild cats.

European Scimitar Cat (Homotherium latidens)

The skull of the European Scimitar Cat. Photo by Ghedoghedo, CC BY-SA 4.0

The scimitar cat is one of the fabled sabre-tooths; a lineage of cats famous for their long, bladed canine teeth. Although the scimitar cat’s fangs were shorter and stouter than some of its more famous cousins, it was no less daunting a predator. It had long front legs and a short tail, giving it an almost hyena-like build, and is interpreted to have been an endurance hunter, running prey down over long distances until they gave in to exhaustion.

It was long believed that scimitar cats became extinct in Europe around 200,000 years ago, but radiometric dating of a jawbone trawled from the North Sea revealed that they survived until at least 28,000 years ago. Check out our article on Doggerland to learn how these fossils found their way to the bottom of the sea.

Cave Lion (Panthera spelaea)

The reconstructed skeleton of an ice age Cave Lion. Photo by Tommy Arad, CC BY 2.0.

Weighing up to 300 kg, cave lions were considerably larger than modern lions (Panthera leo). They were a very successful predator, with fossils and even frozen specimens being found from Spain, across Europe and Asia, all the way into Alaska. They seem to have specialised in cold grassland environments, sheltering from the worst of the weather in caves, and hunted reindeer (Rangifer tarandus) as their primary prey.

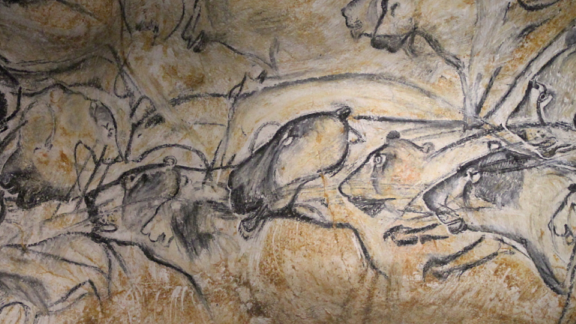

We know a surprising amount about the life appearance and behaviour of cave lions thanks to their depictions in palaeolithic art such as cave paintings and sculptures. They seem to have hunted in groups much like modern lions, but the males lacked the distinctive manes. It has been suggested that lions held an important place in the culture of stone age people, perhaps revered as symbols of strength or feared as heralds of danger.

European Leopard (Panthera pardus spelaea)

A cave painting of a leopard at the Chauvet Cave site in southern France.

Modern leopards are a widespread and adaptable species, though some populations are highly endangered. Distribution of European leopard fossils suggest that, much like snow leopards (Panthera uncia), they preferred living in highlands and associated forests over the open lowlands and steppes. This would help them avoid competition with lions and other low altitude cats, partially by keeping to their own space, and also by hunting different prey.

Like cave lions, leopards appear in ice age art, giving us an insight into their life appearance. One striking feature that can be drawn from these depictions is an apparently spot-free underbelly; a feature not seen in living leopards, but that once again leads to a comparison with snow leopards.

European Jaguar (Panthera gombaszoegensis)

The skull of a European Jaguar. Photo by Ghedoghedo, CC BY-SA 3.0

It seems remarkable to find jaguars in the British Isles, given their modern association with the forests and wetlands of Central and South America, but extensive fossil studies across Europe and Asia have drawn the conclusion that these cats originated in the old world, before migrating across the Bering land bridge into the Americas.

Pound for pound, jaguars are among the most robust and powerful of cats. They are strong swimmers and climbers, and have a crushing bite that can pierce the skull of a prey animal. The European jaguar was more massive than its American cousins (Panthera onca), so was likely even more formidable, and it may have favoured densely vegetated environments, allowing it to approach prey unseen and launch an ambush.

Eurasian Lynx (Lynx lynx)

A Eurasian Lynx patrolling the snowy forests of Bavaria. Photo by Aconcagua, CC BY-SA 3.0.

Still present in parts of Northern Europe and Asia, the lynx is a roughly retriever-sized cat with a distinctive short tail and pointed ears. They are largely nocturnal, solitary and highly secretive, living in dense forest interiors where they hunt rodents, rabbits, birds and occasionally larger prey like deer and boar.

The lynx’s relatively small size and shy disposition have made it a prime candidate for reintroduction and rewilding efforts. Indeed forest parks in mainland Europe where protections have been put in place have seen a recovery of wild lynx populations where they were once hunted. There are ongoing campaign efforts to bring the lynx back to the British Isles in an effort to curb deer populations and restore ecological resilience.

European Wildcat (Felis silvestris)

A Wildcat fends off an intruding photographer. Photo by Charlie Marshall, CC BY 2.0

The smallest of the UK’s historic native cats, wildcats were almost driven to local extinction at the start of the 20th century thanks to habitat loss and persecution, and they continue to struggle to this day. Only a very small population now remain in the remote highland forests of Scotland, with some estimating only a few hundred survive.

Scottish wildcats face extinction in part due to the incursion of feral and free-roaming domestic cats (Felis catus). Domestic cats spread diseases and parasites that the wildcats are not prepared for, but they also interbreed with the wildcats to create hybrid offspring. Genetic examinations of wildcats have found frequent high percentages of domestic cat DNA, leading some scientists to conclude that the species itself may be functionally extinct, existing now only as a genetic legacy in their hybrid descendants.

Domestic cats are by far the most abundant predatory mammal in the UK, with some 10 million moggies sharing our homes and wandering our streets. It should also be made clear that they are not native, and their biology and behaviour makes them a poor fit for British wildlife. Their high numbers, large litter sizes and status as beloved pets, pampered with shelter and medical care, gives them a considerable advantage when they are allowed to wander beyond the homes of their human companions. Tens of millions of birds and rodents are killed by outdoor cats every year, depriving remaining predators like foxes, weasels and birds of prey of their food supply and driving prey species towards extinction.

The humble house cat; beloved companion, steward of cardboard boxes and ruthless invasive killer. Photo by Dane Pavitt

It’s remarkable to think that the UK, currently recognized as suffering a biodiversity crisis, once had a faunal landscape that would be the envy of many great national parks. With an ever increasing public appetite for environmental restoration and species reintroduction, perhaps we might see some of these great hunters, or at least equivalent proxies, make a return to our wilderness.

Further Reading

Rewilding Britain – Eurasian Lynx

Wildlife Conservation Research Unit – Scottish Wildcat Project

Jackie Keily – Big Beasts Of London

A lifelong natural history enthusiast, Dane has built an online following recreating prehistoric life through animation, & is now studying for a Natural Sciences degree while participating in STEM ambassadorship & climate activism.